The Beatitudes and animal liberation

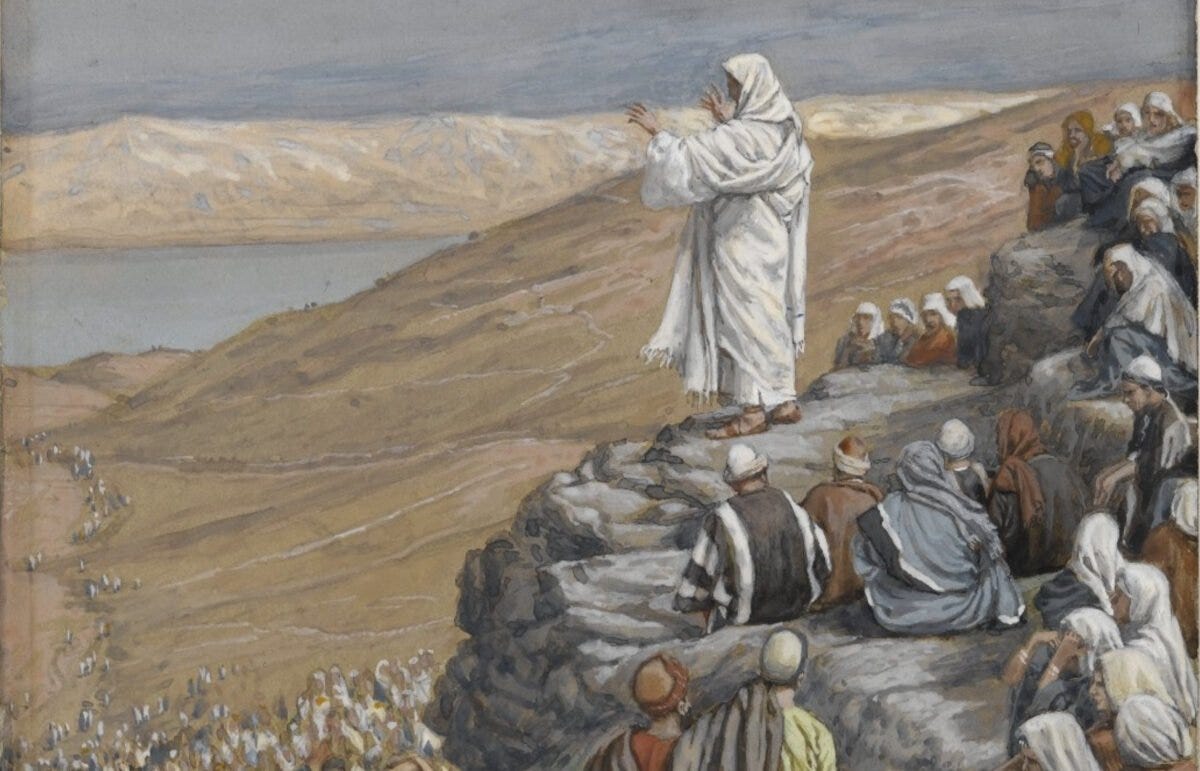

The Beatitudes in the Gospel of Matthew represent the perennialist core of the Christian faith. With a Unitarian approach, that understands Jesus of Nazareth as a human teacher, we can reinterpret these eight blessings in ways the historical Jesus likely never intended. This can provide the basis for a Christian animal liberationism.

In the first beatitude, Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.” The analogous blessing from the Sermon on the Plain, in the Gospel of Luke, is more straightforward. Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor.” The text from the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew is a little ambiguous.

Commentators frequently interpret ‘poor in spirit’ to mean those who have a humble attitude toward God. It implies an openness to the divine will and presence. Only by working to empty ourselves of selfish desires do we leave room for God to fill the space. Similarly, this emptying allows us to recognize the divine presence in others.

When we’re poor in spirit, we can sense God telling us it’s wrong to kill animals and cause them to suffer. When we’re poor in spirit, we can see the divine presence in all, including other creatures, no matter how different they look on the outside. Finally, when we’re poor in spirit, God gives us the energy to pursue animal liberation.

Jesus says, in the second beatitude, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.” Activism on behalf of other creatures signifies a great mourning. When we oppose the slaughter of animals for food, we necessarily mourn the more than one trillion aquatic and land creatures humanity kills every year for this purpose.

In the third beatitude, Jesus says, “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the Earth.” Meekness suggests gentleness and willingness to endure injury without resentment. Fundamentally, animal liberation is about creating a more gentle world. Of course, the blessing demands we use loving, nonviolent means to achieve this.

Jesus says, in the fourth beatitude, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied.” Certainly, activists seeking to improve the lot of their fellow creatures yearn for justice. We hope to abolish a violent system, while we know it is a multigenerational struggle which we won’t live to see completed.

In the fifth beatitude, Jesus says, “Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy.” The animal liberationist project is a merciful one. We are trying to spare countless creatures from unimaginable torture and premature death. There is no human equivalent to the amount of suffering we wish to relieve.

Jesus says, in the sixth beatitude, “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.” For activists, like everyone else, there is always the temptation to do the right thing for the wrong reasons. Given how little earthly reward there is for animal-liberationist work, I like to think our motivation is largely pure.

But the more this is true, the more effective we are. For instance, when we’re pure in heart, we’re able to distinguish between strategies that help other creatures and those that feed our egos. This is an internal battle all activists grapple with and necessarily results in a periodic reassessment of tactics.

In the seventh beatitude, Jesus says, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called the Sons of God.” Animal liberationists are essentially peacemakers, standing in opposition to humanity’s war on other creatures. No war between members of our species has ever involved violence on such a scale.

Jesus says, in the eighth beatitude, “Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.” Activists have risked death, imprisonment and arrest on behalf of other animals. Even those who are less confrontational in their work frequently risk social ostracism.

Again, the Beatitudes are the heart of Christianity. When we adopt a Unitarian perspective, we can extend the compassionate teachings of Jesus in ways the historical figure probably never imagined. In this way, the faith can remain relevant for those with different ethical concerns than his first-century audience.