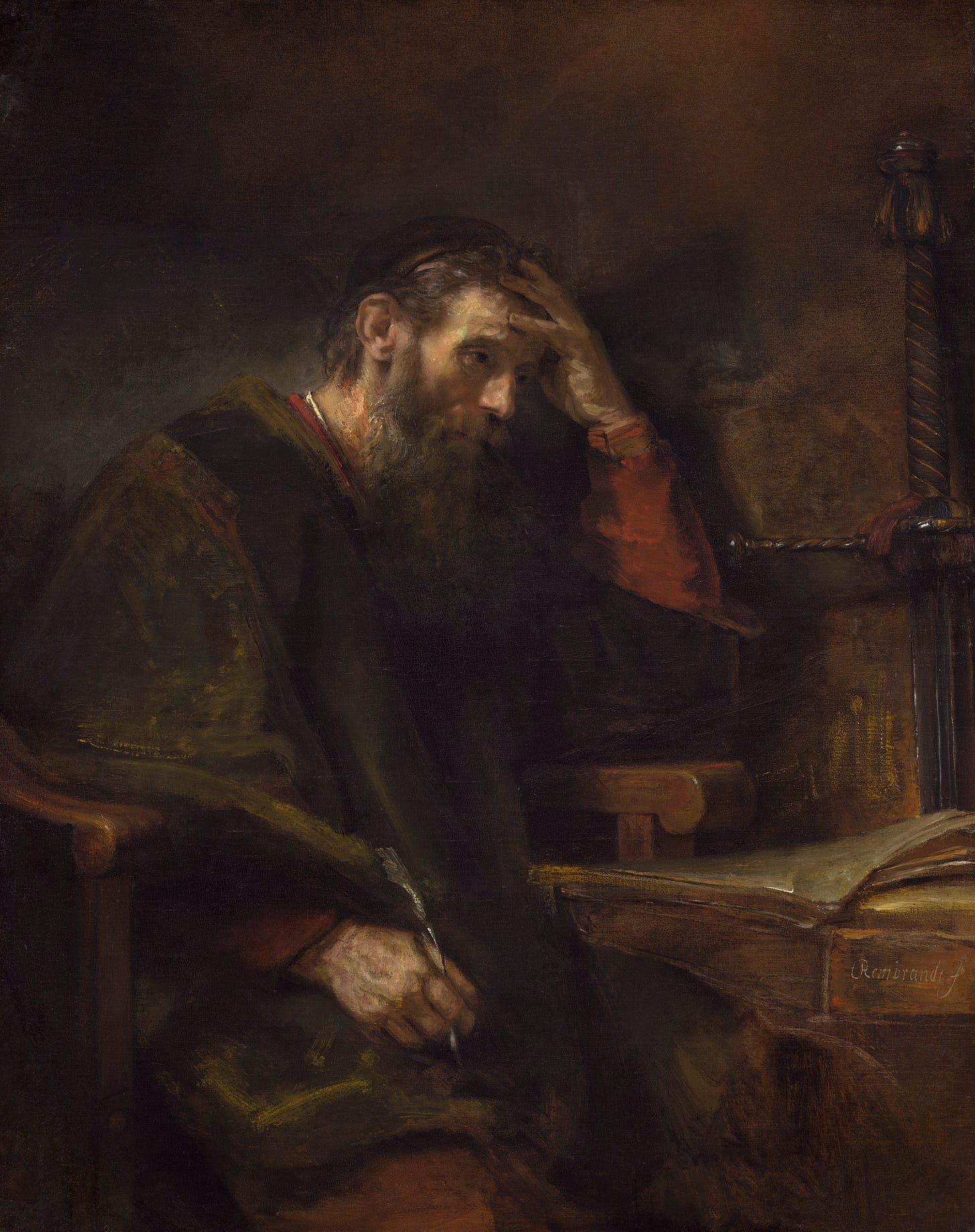

Animals and Saint Paul

Saint Paul is often regarded as a particularly troublesome writer for those who try to reconcile animal liberation and Christianity. For instance, there appears to have been a debate in the early church about the importance of vegetarianism. Paul was on the wrong side of this, but he was quite accommodating toward practitioners of the diet.

“One person’s faith allows them to eat anything, but another, whose faith is weak, eats only vegetables,” Paul writes in the Epistle to the Romans. “All food is clean, but it is wrong for a person to eat anything that causes someone else to stumble. It is better not to eat meat or drink wine or to do anything else that will cause your brother or sister to fall.”

Despite his qualified opposition to vegetarianism, I believe there are other elements of Paul’s writing that could be helpful in constructing an anti-speciesist faith. In particular, there are a number of passages that could be interpreted as offering a pantheistic or panentheistic conception of God.

Pantheism is the belief that the universe is God. Panentheism is slightly different, referring to the belief that the universe is God, but God is also greater than the universe. Obviously, the universe includes animals. And if one believes animals contain some type of divine spark, you’re probably going to treat them with a degree of reverence or respect.

There are a lot of reasons why classical Hinduism is more animal-friendly than classical Christianity. From a materialist perspective, the society that produced the Hindu scriptures seems to have been less animal dependent, due to environmental factors, than the society that produced the Christian scriptures.

But from a theological perspective, one of the reasons classical Hinduism is more animal-friendly than classical Christianity is the former is much more clearly pantheistic or panentheistic. Still, there are resources in the Bible with which to build a pantheistic or panentheistic Christianity. Paul offers some of them.

I should note scholars are unsure if he wrote all the texts attributed to him. That said, in the Epistle to the Colossians, Paul writes the remarkable statement, “Christ is all, and is in all.” To be fair, this is preceded by a sentence that could be read as qualifying “all” to mean only humans or human Christians.

“Here there is no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free,” Paul writes. But couldn’t “all” be read as not just this diverse collection of humans, but everything in the whole universe, including animals? The alternative, which would dramatically limit God’s presence, seems almost sacrilegious.

In the same text, Paul writes of Christ: “For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.”

If all things were created in God, and all things hold together in God, doesn’t that mean God, in some limited way, is in all things? That reads like pantheism or panentheism to me. In my view, such an interpretation could form the basis of a more animal-friendly Christianity.

As I wrote in a recent article about Pope Francis’ second encyclical, “How must we remake society if [some part of God] is in the chicken killed for meat, the rat tortured for science, the deer shot for sport, the elephant caged for entertainment, or the cow slaughtered for clothing?”